Although Orlando in the mid 1900s was no Selma, Alabama, or Little Rock, Arkansas — places that are synonymous with the violent struggles of the civil rights movement — Orlando was still full of segregation, strife, and systemic white supremacy.

The newly constructed Interstate 4 cut off Parramore, a traditionally African-American neighborhood, from downtown and white society. White kids went to better schools and their parents had better opportunities.

While the brutality that occurred in Orlando was not as notoriously publicized, there were protests — black high school students arrested for trying to order from the lunch counter at Woolworth’s — and violence — in 1920 a white mob killed African Americans in Ocoee in an effort to suppress black voting, to cite just one example. But by midcentury, the city’s officials tried to alleviate tensions. The City Beautiful attempted to project an image of peaceful coexistence to the outside world.

There was some truth to this projection, at least relative to the rest of the South. Segregated as it was, Parramore thrived, full of culture, commerce and wealth. And at the center of the hub that was Parramore stood Jones High School, the black high school that was established in 1895.

“Jones was central to the community,” says Ben Brotemarkle, executive director of the Florida Historical Society. “Everybody in the community went there. It has had some pretty prominent graduates over the years. Of course, Chief Wilson was a pretty big part of that.”

By Chief Wilson, he means James Wilson, who taught music at Jones and led its marching band to greatness from 1950 to 1990. Jones had the best band in town — even with less resources and support — and everyone knew it.

Wilson, along with his unlikely friend Delbert Kieffner, the white bandleader at Edgewater High School, asked the city and county for equal funding together for both groups, making it all but impossible for politicians to give Jones less. And finally in 1964, Wilson and his band — about 100 parents and students in total—took the pivotal trip to New York City that would fundamentally reshape Orlando.

“I might be taking too much credit, but we were the catalyst for the integration of the whole community,” Wilson once said.

He wasn’t taking too much credit. If anything, Wilson was taking too little. Not only did the New York World’s Fair trip help facilitate the desegregation of Orlando, but the harmonious image it sent to the world might have prodded a certain theme park entrepreneur to give Orlando a closer look.

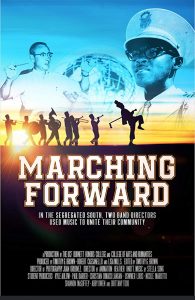

This is the story that the new documentary Marching Forward aims to tell. The film covers more than the World’s Fair trip. It’s also about the nuances of race relations in Orlando during the latter days of Jim Crow, and the unlikely friendship forged between Wilson and Kieffner. It’s about tireless devotion to musical excellence and the foundation of traditions that remain to this day. And it’s about how the synchronicity of all those things may have helped lure Walt Disney World to Central Florida.

Basically, it’s a complex, layered story, difficult for even a skilled documentarian to pack into a 60-minute feature. The documentary is all the more remarkable when considering that it was pieced together by two professors and a handful of UCF students, most of whom had no background in documentary filmmaking — and even more so when you realize that it’s an outstanding film on its own merits, smartly crafted and edited, with poignant interviews interspersed with archival footage and animation.

“I think knowing the history of your community can always make you feel more connected to where you’re living,” Brotemarkle says, on the importance of this moving film.

This is the fourth documentary that associate professor of history Robert Cassanello and associate professor of film Lisa Mills ’99MA have made in the past decade along with students in their Honors Advanced Documentary Workshop class. Their 2012 film, The Committee, won a Suncoast Emmy Award and their 2014 film, Filthy Dreamers, also won an Emmy in the 37th College Television Awards.

But Marching Forward, which is scheduled to premiere at the Florida Film Festival in April, is Cassanello, Mills, and their students’ most ambitious endeavor. That’s not just because it’s their first feature-length film, meaning it’s twice as long as their other projects, but also because it’s the first that examines important events that took place right in their backyard.

“For the previous films, we consciously chose a subject matter outside the area,” Cassanello says. But for this project, they wanted to do something about the community. And in the fall of 2015, Cassanello was part of a local panel that was doing a retrospective on the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts. One of his co-panelists was an Orlando Sentinel writer who brought up the Jones band and its trip to the World’s Fair in 1964. Cassanello and Mills were intrigued.

“We’ve seen many documentaries about the well-known heroes of the civil rights movement. Chief and Del are the unsung heroes. They took risks and did what was right despite the color lines of the time. That took courage,” says Cassanello.

Read the entire article, originally published in UCF’s Pegasus magazine, here.